(This article by Tony Ware originally appeared in the January 2021 issue of Military Officer, a magazine available to all MOAA Premium and Life members. Learn more about the magazine here; learn more about joining MOAA here.)

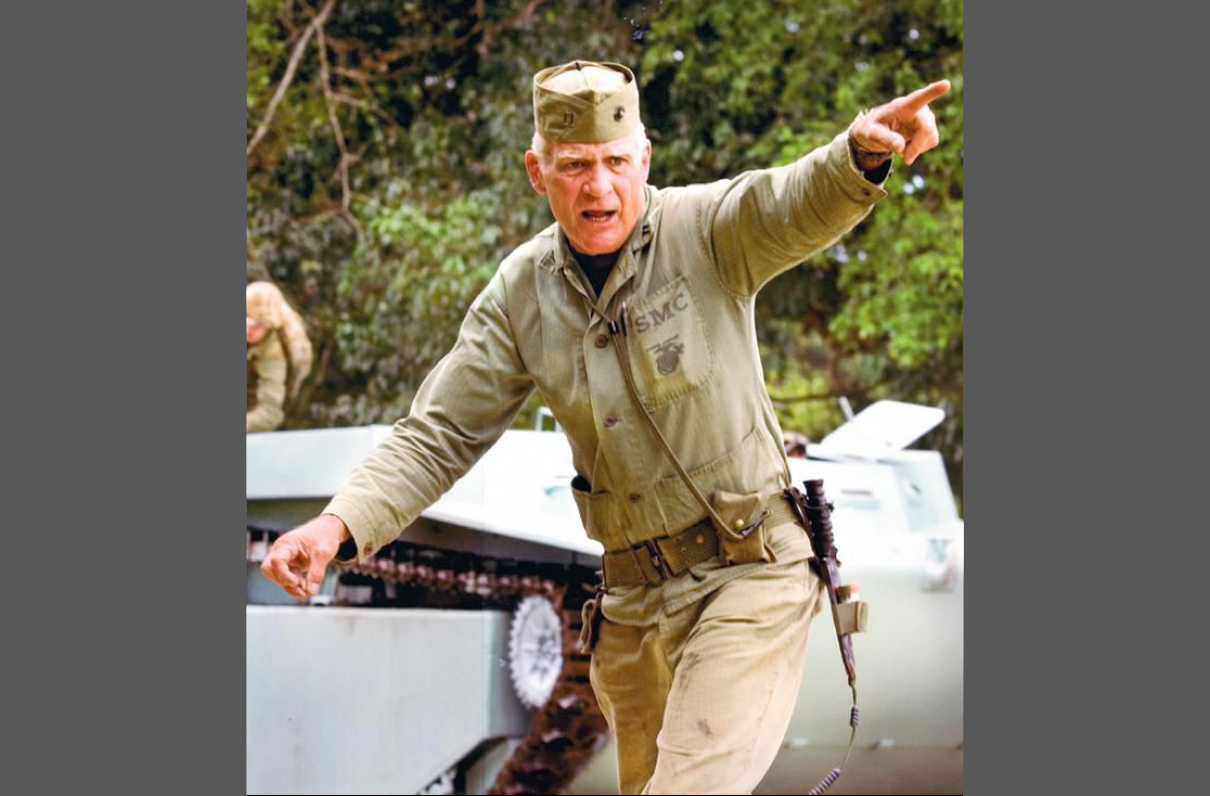

Capt. Dale Dye, USMC (Ret), enlisted in the Marine Corps in 1964, spending 20 years in the service, including multiple tours of Vietnam and assignments to the Middle East.

Dye retired from the military in 1984, but he never left it fully behind. Lamenting how movies portrayed grunts, he founded Warriors Inc., a technical advisory firm, to provide entertainment with insight. Dye first made his mark consulting on Oliver Stone’s 1986 Oscar winner Platoon — taking 33 actors into the jungle for weeks so they could live closer and dig deeper into an actual soldier’s mentality. He has since worked on dozens of award-winning productions. Most recently, he helped with Tom Hanks’ Greyhound, which debuted in July 2020 on Apple TV+.

Military Officer spoke with Dye to discuss his method. The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

[RELATED: Tom Hanks Talks World War II Film 'Greyhound']

Q. When you transitioned to civilian life, did you see the film industry as providing you with an escape from what you’d experienced in the field?

A. “Escape” is the wrong word, because what it actually provided me with was another reality: an occupation where I could apply what I knew and renew my warrior spirit. ... So, while it may be partially about fantasies, Hollywood intrigued me and allowed me to further an agenda. I had seen practically every military movie, but most of them pissed me off because I didn’t think it was an accurate or fair portrayal of the men and women that I served with.

Q. The first film you consulted on was set in 1967 during the Vietnam War, which you personally experienced on multiple tours of duty. Was it initially a challenge to work on films set outside those campaigns?

A. No, because there’s a certain continuity to what I do. I’ve gone all the way back to ancient Greece in Alexander. I did the French and Indian War, 1757, in The Last of the Mohicans. There have been all the fronts in between, WWII parachute infantry in Band of Brothers, or the Battle of the Atlantic in Greyhound, and then actually hundreds of years into the future for Starship Troopers. There’s a warrior spirit in a soldier, a certain mentality that is common, and that’s the experience I train.

[MORE MOAA INTERVIEWS: The Outpost's Orlando Bloom | The Right Stuff's Jake McDorman | Gary Sinise]

Capt. Dale Dye, USMC (Ret), left, gives actor Damian Lewis feedback on the set of the acclaimed HBO series "Band of Brothers" in England. (Photo courtesy of Damian Lewis)

Q. How do you adapt your technique to different eras?

A. First, I have to do an enormous amount of research. And as a writer, a storyteller, and amateur historian, I like that. ... So, what it requires of me is to be very facile mentally; I have to imagine a lot of things. Then the goal is to get actors into a place as physically and mentally similar to the story’s setting as possible — what we call “full immersion.” By that, I mean you separate them from any trappings that suggest whatever year it is besides the one you’re training for. You isolate them and make them live that world. ... I tell them to not only keep their eyes open, but keep their hearts open; when you experience something unusual, like absolute, utter exhaustion or sorrow, absorb it; remember that, and when the time comes for you to display it, you can reach back and touch that baggage.

Q. What are benchmarks of success for breaking down an actor’s walls?

A. It’s body language. It’s when you overhear them, talking to each other, finding the black humor. Every day, during a training evolution, usually after evening chow, I have what’s called a stand down. It’s the actors’ one opportunity to ask any question, and I will not stop until I have provided that answer. You can see their mind opening up as they ask, “How does it feel to get shot? What does shrapnel do to you? How does it feel when they hit you with morphine?” … Then, as you continue through the training, you do what every company gunnery sergeant, every company commander and platoon leader has ever done: Observe your people very closely and catch flaws, catch misunderstandings, and pull them aside and get them straight on it.

Later, on set, me and my NCOs get to them while they’re getting into uniform, and we’ll bark — we’ll do the things that they remember from their training. And we try to do things like march them to and from lunch, for instance, and march them onto the set — reinforce their experience as a unit. It’s leadership in the raw, and I dearly love doing it.

[RELATED: Dale Dye on Military.com's Left of Boom Podcast]

Q. It’s one thing to bark at someone assigned to your boot camp, but another to ask a director to trade their artistic license for more authenticity. How do you approach sticking points?

A. You have to be a bit of a dramatist yourself and understand that some things are being done to advance the storyline. But usually, if it’s outrageous, you can convince the writer and director that doing it in a manner that real soldiers would do it is often just as dramatic and effective. I think a person is a fool not to understand the massive impact of popular media — movies and television in particular, but video games ... as well. And anything I can do to impart insight into the service and sacrifice of American men and women in uniform, I want to do.

No matter what I’m working on — whether it’s a miniseries or a 30-second commercial — I want the end result to be people understanding that military men and women are human, with human foibles and human concerns. Despite that, they are the type of people who are willing to lay their lives on the line; they know there is something larger and more important than themselves. And they are willing to serve an objective even if it’s painful — because it’s worth it.

Tony Ware is a freelance writer and editor based in Northern Virginia.

Support The MOAA Foundation

Donate to help address emerging needs among currently serving and former uniformed servicemembers, retirees, and their families.