Brig. Gen. Carol Eggert, USA (Ret), was in Baghdad in 2009 when a rocket came hurtling into the hull of her vehicle, just inches from her head. A huge boom shook the mine-resistant, ambush-protected vehicle, knocking her unconscious.

As Eggert slowly came to moments later, everything was quiet and still as the vehicle lay smoking and disabled.

Even in her fog, Eggert realized others around her were hurt. She went to aid the soldier sitting in front of her who had suffered a shrapnel injury to his arm, but the simple act of applying a bandage was unusually awkward and difficult for her.

Eggert, eventually shook off her daze from the incident and for the rest of her deployment, though she said she knew something was wrong. What she didn’t know at the time was that she had suffered a traumatic brain injury (TBI) during the rocket attack, and her life would never be the same again.

Thirteen years after the incident, memory loss, difficulty organizing, and a hyper startle reflex are all part of Eggert’s daily life and may be symptoms of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). To help those who may have similar experiences in the future, Eggert decided to donate her brain to Project Enlist, a program started by the Boston-based Concussion Legacy Foundation (CLF).

[LEARN MORE: Project Enlist]

Project Enlist aims to jumpstart research on TBIs, CTE, and post-traumatic stress in veterans. Unfortunately, the only way to definitively diagnose CTE is to study the brain of a deceased person.

‘We Have to Figure Out CTE’

CTE research got a boost thanks to the efforts of former college football player and professional wrestler Chris Nowinski and his physician, Dr. Robert Cantu, who co-founded the CLF in 2007.

Four years earlier, Nowinski had suffered a bad concussion after accidentally being kicked in the head during a wrestling match. He began getting headaches, and that plus a sleeping disorder meant he was unable to push himself physically without feeling ill. It took meeting with Cantu to understand his condition better and to get a glimpse into what we now know as CTE.

“[Cantu] was the eighth doctor I saw but the first person to understand what I was going through,” said Nowinski. “All of the doctors had asked how many concussions I had, and I said zero. … But I don’t know how many times I saw stars or had double vision. That happened all the time. [When Cantu asked me that], that was a lightbulb moment.”

Nowinski and Cantu penned a book called Head Games: Football’s Concussion Crisis from the NFL to Youth Leagues (Drummond Publishing Group, 2006). However, CTE did not make headlines in the sports world until NFL star Andre Waters’ death from suicide a few months later and the subsequent decision by Waters’ family to donate his brain to science.

Former professional wrestler Chris Nowinski, left, co-founded the Concussion Legacy Foundation to help those like him who have experienced — and continue to suffer from — brain injuries. (Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images)

“I made the deal [with his family], saying that if Andre’s brain came back positive [with CTE], we would tell the world,” said Nowinski. “For The New York Times to put that story on the front page, that’s when I realized that we have to figure out CTE.”

Wide-Ranging Impact

Since the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank opened at Boston University (BU) in 2008, researchers have analyzed 1,250 brains from deceased individuals, including 233 from veterans. Of the 1,250 brains, 700 have been determined to have some form of CTE, including 60% of the veterans’ brains.

While roughly one-third of the 50 brain donors who suffered blast injuries like Eggert were diagnosed with CTE, repeated trauma to the head, albeit minor in many cases, is the most likely cause of CTE, said Dr. Ann McKee, chief of neuropathology for VA Boston Healthcare and director of the BU CTE Center. CTE can be a result of playing contact sports for more than five years, continually participating in military training exercises, or experiencing combat scenarios that involve trauma to the head. These activities can include anything from artillery training to repeated exposure to IEDs.

Brig. Gen. Carol Eggert, USA (Ret), shown here during service and in her current role as senior vice president of military and veteran affairs for Comcast NBCUniversal. (Courtesy photos)

The majority of those diagnosed with CTE are individuals who played contact sports, whether they were in the military or not, said McKee. Future brain donor and retired Army Maj. Charlie Bailey often experienced blows to the head as a high school and collegiate soccer goalie. Plus, he had dozens of close calls with IEDs. He said he and his fellow soldiers would often get knocked out or dazed by an IED explosion while in a vehicle.

“During that time period, the climate wasn’t one to encourage soldiers to seek help [for TBIs],” said Bailey, a MOAA member. “The way we joked about shaking off an IED explosion was like how a linebacker shakes off a hit in football. There were a number of times we experienced IED attacks inside armored vehicles. Everyone is knocked out, you come to, and then check on one other.”

Unfortunately, Bailey got too close to an IED just a month before the end of his 12-month deployment in Iraq. In June 2006, an IED went off next to his vehicle. Bailey was in the hatch when the explosion occurred, and the shrapnel from the blast blew off part of his skull and nearly took out his left eye. He underwent emergency surgery and had his eye removed.

Despite being diagnosed with only a minor TBI, Bailey suffered from depression and avoided social situations for much of the next 10 years. In 2016, he experienced a grand mal seizure while drifting off to sleep. The attending doctor at an Army medical hospital in Hawaii gave him some shocking news about his health that would lead to his medical retirement from the Army in 2017.

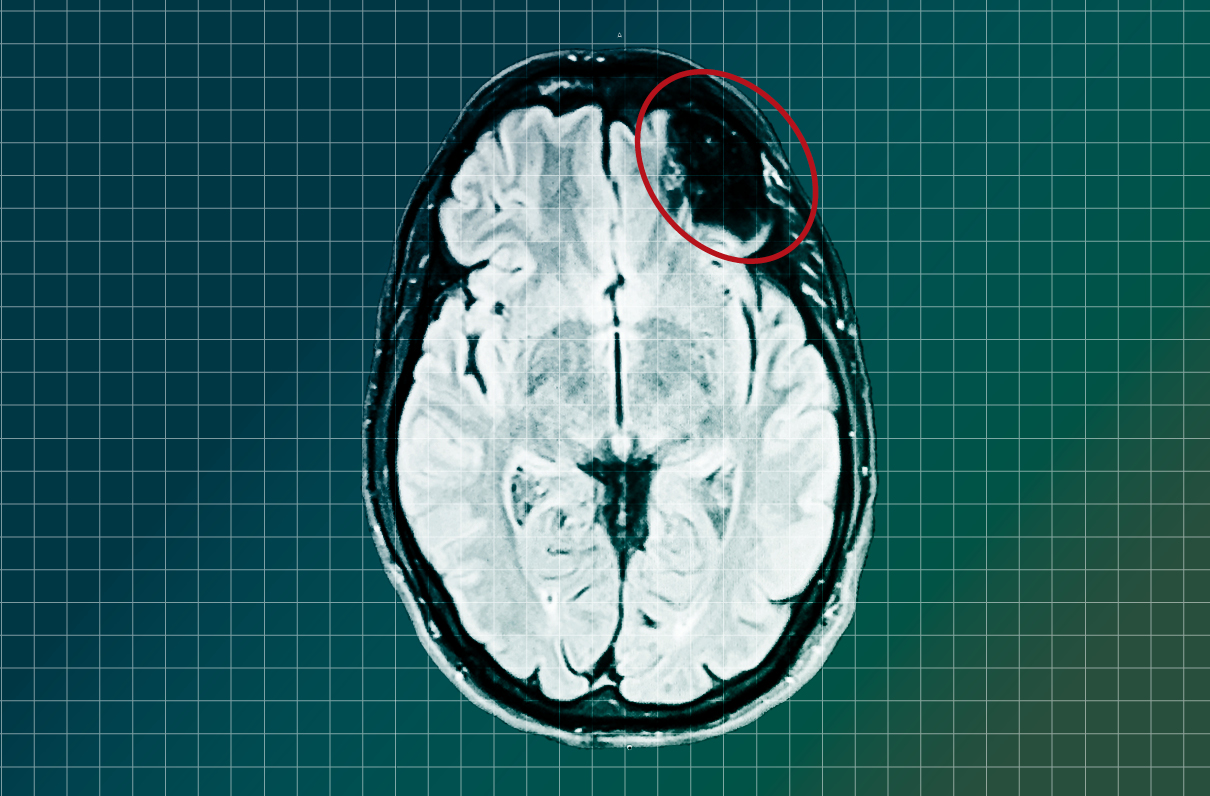

“The doctor said, ‘There is nothing mild about your injury to your brain,’” Bailey said. “I saw my wife breaking down in tears, and I sat there in shock by the scope of the injury. A very large portion of my front left lobe of my brain was black, which meant it was dead.” Bailey, who serves on the CLF Veteran Advisory Board, believes the doctors at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center may have underestimated the extent of his brain injury.

“I lost my left eye, there was shrapnel all over my face,” said Bailey. “They were way more concerned [about] getting me a fake eye and treating my external wounds than whatever happened to me internally.”

An IED explosion in Iraq in 2006 left Maj. Charlie Bailey, USA (Ret), with no left eye and also caused a brain injury that was discovered years later. (Courtesy photos)

Individuals who experienced the same things Bailey did in Iraq have had difficulty leaving the war behind, he said. He knows of at least two soldiers in his platoon who committed suicide and said several are still on a psychological journey despite being long removed from deployment.

Bailey admits his own road was rocky at times. That’s why he is thrilled with the work being done by the CLF to assist the veteran community, both now and in the future.

“If there is anything I can do to help support their mission,” he said, “I am 100% behind it.”

Overcoming the Stigma of Seeking Help

Brain injuries like Eggert’s or Bailey’s were not well known 15 years ago and were sometimes ignored by servicemembers, even to their own detriment. It took that fateful day in Hawaii for Bailey to realize his health was hanging in the balance due to the trauma inflicted on his brain. This was despite the symptoms that lingered, ones that were leaving an impression on his family.

“That first seizure in 2016, that was a physical manifestation of everything that happened over the course of those last 10 years,” said Bailey. “In essence, it was a blessing because it was the first time that I was forced to acknowledge that I had been injured, that I wasn’t invincible.”

Eggert displayed the same hesitancy to get treated. To this day, she doesn’t consider herself a TBI victim and feels fortunate she can carry on a somewhat normal life as the senior vice president of military and veteran affairs for Comcast NBCUniversal.

But Eggert is happy she made the choice to seek assistance from the VA even though it took her six years to do it. She encourages all servicemembers and veterans, especially women, to look for guidance after experiencing a traumatic event.

Eggert, who also serves on the CLF Veteran Advisory Board, is particularly hopeful that more women will pledge their brains to science so future veterans can benefit from the research.

“Let’s acknowledge TBI, let’s acknowledge what we have experienced,” she said. “And let’s help those organizations that are trying to make things better for those servicemembers that come behind us.”

Military Officer Magazine

Discover more interesting stories in MOAA's award-winning magazine.