(This article by Latayne C. Scott originally appeared in the February 2026 issue of Military Officer, a magazine available to all MOAA Premium and Life members who can log in to access our digital version and archive. Basic members can save on a membership upgrade and access the magazine.)

It was like a scene from a 1950s movie: The beautiful young secretary saw the tall, dark-headed young man in uniform standing across the room. Their eyes met and locked.

The rest was history.

Except this was no movie, and the young woman was Ingrid Marie Runge. As a teenager, she survived the 1945 Allied bombings of Berlin, she told Military Officer. Some of her most vivid memories are of crowds of neighbors, elbow to elbow in a basement, gingerly avoiding the boiler in the corner and trying to distract themselves from the nightly explosions rocking the building.

Nine years later, in a different crowded room in Berlin, she saw that young man in his uniform.

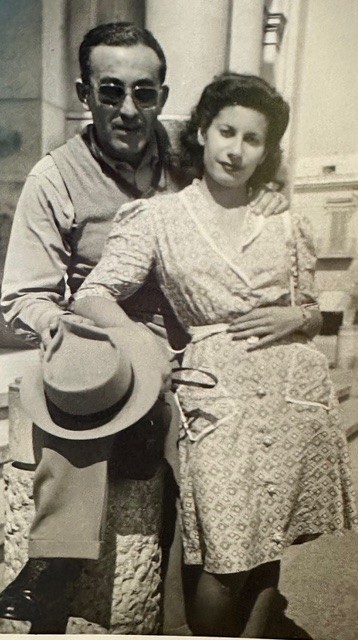

George Sondergaard, then a master sergeant in the U.S. Air Force, had just announced his plan to become a monk once he would return home to Bronx, N.Y. But the fateful moment George met Ingrid, he knew the solitary life of monasticism was “out the window,” a friend of George recalled the veteran as saying.

George Sondergaard, left, met Ingrid Marie Runge, right, when he was in the Air Force. (Photo courtesy of Ingrid Sondergaard)

Aided by the fact George spoke several languages, including German, their whirlwind romance turned into marriage and immigration to the U.S.

Remembering the Relationships

Today, the stories of war brides are vanishing with them. This is especially true for those who married around World War II and are still alive, likely at over 95 years of age; those from the Korean War era, like Ingrid Sondergaard, are also likely in their 90s, if not older. Brides from the Vietnam War era are estimated to be at least in their 70s.

But there are efforts to save these stories of wartime and love. Several online projects feature their faces and their voices.

Japanese war bride Chiyohi Creef, right, shares stories of her life with her late husband, a U.S. soldier who served in Japan. (Karen Kasmauski via Smithsonian Institution)

The accounts are often visceral: Lilly Yuriko Krohn, for example, only escaped the Aug. 6, 1945, Hiroshima bombing because she was late for work that day. A decade later, she married a master sergeant in the U.S. Army and immigrated, eventually settling on a farm in southern Indiana.

Online language-learning portal Babbel provides audio and video recordings as well as transcripts of war brides’ stories from Japan, France, Belgium, Italy, and the Philippines.

Online language-learning portal Babbel provides audio and video recordings as well as transcripts of war brides’ stories from Japan, France, Belgium, Italy, and the Philippines.

For instance, an Italian woman named Emilia Zecchino had already been through major transitions before she met her husband to be. She’d spent time in an Ethiopian concentration camp as a child and returned to bomb-ridden Italy in 1943. Thus, when she met an Italian-American servicemember (both pictured), a move to New York was not the kind of transition it was for many other war brides who had never lived outside their native countries.

[BABBEL.COM: War Brides]

Another resource, “The War Bride Experience,” is meant for fifth grade through college and stems from over 100 interviews and a decade of research. It’s free and designed to spark conversations about immigration, and it offers a teacher’s guide and 40 short audio stories. Part of that is “Japanese War Brides: An Oral History Archive,” which provides fascinating “stories from across the U.S. as told to a daughter of a war bride,” Kathryn Tolbert.

Then there’s Yayoi Winfrey’s award-winning film series War Brides of Japan, a docu*memory. The project chronicles the experiences of her father, 97 years old as of this writing, and her deceased Japanese-born mother, Lily.

“My dad was a soldier, but my mom was such a survivor,” Winfrey said of her mother, who survived both the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 and the 1945 firebombing of Tokyo before meeting Winfrey’s father. The earthquake and the bombing each killed about 100,000 people, although estimates vary.

Winfrey found Japanese brides very reticent.

“I personally interviewed 14 Japanese war bride families,” she told Military Officer. “Out of that number, only five brides were willing to speak. I ended up with only three who spoke on camera.”

For her part, Leah Spellman Berger organized a reunion of war brides in 2019. She says about a million women from around the world married U.S. servicemembers between 1942 and 1952, and Spellman was able to connect with about a dozen.

She interviewed them after the gathering, and the stories are available online as part of her “World War II War Brides Project.” (For more by this researcher, see her article “Leaving Home for Love” in the February 2020 issue of Military Officer.)

The Smithsonian Institution also has a traveling exhibit on the history of war brides. Its limited-time multimedia display, “Japanese War Brides: Across A Wide Divide,” began in late 2024 and will run through summer 2028, with upcoming showings in New York, Louisiana, California, and Michigan.

The exhibit includes audiovisual kiosks, historical objects, memorabilia, and an educators’ guide. These features tell the stories of the nearly 45,000 Japanese war brides from the World War II era — “the largest women-only immigration event in U.S. history.”

“Their experiences altered U.S. society and reshaped communities by challenging foreign policy, immigration laws, and race relations,” according to the exhibit’s website.

Entering a Foreign Land

Just as language proved to be no barrier for the Sondergaards, neither was America’s immigration policy. The War Brides Act of 1945 had paved the way for both foreign-born spouses — about 300,000 (and some were men) — and the children of servicemembers to come to the U.S. Before the War Brides Act, the Immigration Act of 1924’s strict quotas and country-specific bans had made immigration, especially for most East Asians, nearly impossible.

Although the War Brides Act helped smooth the path for foreign-born spouses to enter the U.S., there were also downsides. For instance, marriage didn’t automatically confer citizenship nor the associated public assistance.

Loneliness and homesickness also played their parts.

Women attend a Western-inspired brides school in Tokyo in the 1950s. (Photo courtesy of Swartz family via Smithsonian Institution)

“Japanese war brides came to the states immensely disliked due to Japan starting the war,” Winfrey said. “Plus, English was harder for them to grasp, and a lot of European women already knew how to speak it.”

Winfrey’s father is Black, which further complicated the process of integration into American life due to prejudice. But she said there was an unexpected bonus.

“I realized that white fathers just expected their kids to assimilate even though they were half Japanese,” she said, noting they often didn’t learn their mothers’ language and customs. “But the Black fathers, who were still struggling with segregation until 1965, just assumed their children wouldn’t be a part of the mainstream. So a lot of those mothers taught their kids customs, culture, and language.”

Within a year of the massive immigration of war bride families to the U.S., a third of those marriages ended in divorce, according to a 2023 report on the research database EBSCO.

However, the report noted, “the majority of the marriages that lasted through the first year continued to last. Many of the war brides not only preserved their marriages but also became valuable members of their communities and contributors to American culture, which became even more diverse as a result.”

A Success Story

So what happened to the Sondergaards, the starstruck couple who met in Berlin?

Their happy marriage would last 58 years, produce six children, and lead to the founding of a parish in the desert of New Mexico. George died in 2013. Ingrid, now 92, lives in Albuquerque, N.M.

The parish reflects the couple’s international roots, with parishioners born in over a dozen foreign countries.

“I don’t know why God saved me during the war, but I know it was for the man I was in love with,” Ingrid said, “and he was in love with me.”

Latayne C. Scott is an Albuquerque, N.M.-based author of 31 books and thousands of shorter works.

Military Officer Magazine

Discover more interesting stories in MOAA's award-winning magazine.