(This article by Lt. Col. Patrick J. Chaisson, USA (Ret), originally appeared in the February 2026 issue of Military Officer, a magazine available to all MOAA Premium and Life members who can log in to access our digital version and archive. Basic members can save on a membership upgrade and access the magazine.)

Operation Desert Storm, the liberation of Kuwait by American-led coalition forces, concluded 35 years ago this month. An international response to Iraq’s August 1990 invasion of Kuwait, this conflict is now considered the United States’ first major foreign crisis following the end of the Cold War.

During a six-month preparatory phase codenamed Desert Shield, more than 500,000 American servicemembers deployed to the Middle East. Then, in January and February 1991, U.S. and allied troops initiated a massive air, sea, and ground offensive called Operation Desert Storm.

Their goal: evict the Iraqi Army from Kuwait.

One Gulf War veteran, MOAA member Col. Paul Conte, USA (Ret), was a first lieutenant in 1990 serving with 4th Battalion, 3rd Field Artillery Regiment (4-3 FA), 2nd Armored Division (Forward), stationed in Garlstedt, Federal Republic of Germany. When Iraq invaded Kuwait, Conte remained unconcerned, he told Military Officer in a recent interview to recount his role in the campaign.

He figured sending American rapid deployment forces into the region would compel Iraqi strongman Saddam Hussein to abandon Kuwait. Instead, Saddam chose to stay and fight. Even as diplomatic efforts aimed at finding a peaceful solution to the crisis continued throughout autumn 1990, an American-led coalition began moving combat forces into neighboring Saudi Arabia. This included the 2nd Armored Division (Forward).

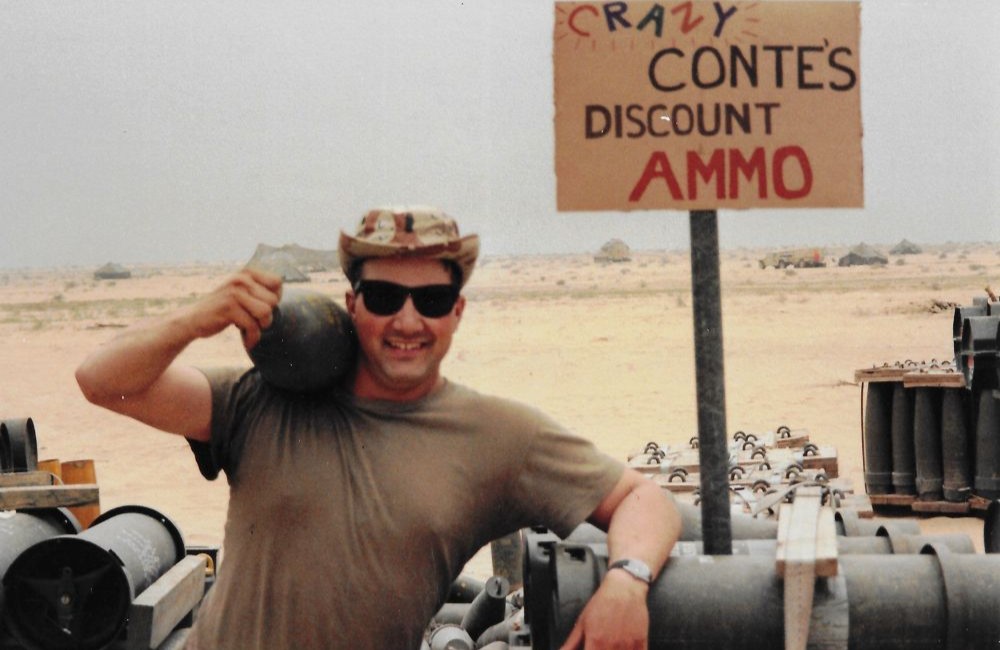

Then-1st Lt. Paul Conte poses at a unit ammo point shortly after the end of the ground war in 1991. (Photo courtesy of Paul Conte)

Conte remembered being alerted for deployment that November. He said his brigade — equipped with modern M1A1 Abrams tanks and M2A2 Bradley Fighting Vehicles — would “round out” the Kansas-based 1st Infantry Division, becoming its third brigade once in theater.

By mid-January 1991, 4-3 FA’s artillerymen found themselves applying tan paint to their M109A2 self-propelled howitzers, M998 Humvees, and other vehicles at the Saudi port of Al Jubail. A few days later, Conte’s gunners moved deep into the trackless Arabian desert to a point named Tactical Assembly Area (TAA) Manhattan where they performed final pre-combat checks.

As battalion ammunition officer, Conte witnessed firsthand the mental adjustment his soldiers needed to make before entering battle.

“We gave them everything,” he said, “artillery projos [projectiles], small-arms ammo, AT-4 anti-tank rockets, even demolitions.”

Unit NCOs, Conte said, enforced high safety standards while helping their troops adopt a proper wartime mindset.

At TAA Manhattan, Conte acquired a GPS receiver — a new and rarely issued device, at the time — to mount in his unarmored Humvee. That GPS put Conte in harm’s way after 4-3 FA moved up to the Iraq-Saudi border in February.

“Since I had a [GPS],” he said, “I was expected to accompany two artillery raids that took place before the start of the ground war.”

The raids on Feb. 21 and 23 each involved a battery of eight howitzers crossing the border at night, moving into position, and shelling the enemy, Conte said. Due to the danger of Iraqi counterbattery fire, 4-3 FA’s gunners would “shoot and scoot,” departing rapidly once the mission ended.

An M109A2 self-propelled howitzer belonging to 4th Battalion, 3rd Field Artillery, moves across the desert. (Photo via Lt. Col. Patrick Chaisson, USA (Ret))

Busy with their own duties, Conte’s soldiers remained largely unaware of the five-week air campaign that was methodically pulverizing Iraq’s command nodes, logistics hubs, and high-value targets. Beyond the horizon, other coalition forces — special operations troops; Marines, airmen, and sailors; allied soldiers from the U.K. and France; and Arab partners — all prepared for G-Day, the start of the ground offensive.

It began before dawn on Feb. 24, when 1st Infantry Division troops secured the “Berm,” a fortified earthen wall separating Saudi Arabia from Iraq. Then 4-3 FA passed through this breach and immediately began firing in support of U.S. units already in contact with the foe.

Conte’s handwritten notes show his battalion’s 24 M109A2 howitzers fired an astonishing 3,950 “projos” that afternoon.

While the enemy troops encountered on G-Day were quickly vanquished, Iraq positioned its best formations — the vaunted Republican Guard — well behind the border. American ground forces ran into these elite soldiers on Feb. 26.

Fighting in rainy conditions, the U.S. Army’s 2nd Armored Cavalry Regiment (ACR) defeated elements of Iraq’s Tawakalna Division at the Battle of 73 Easting. When combat ceased that evening, thousands of enemy troops had been killed or captured as well as 400 tanks and other vehicles destroyed.

Meanwhile, maneuvering south of the 2nd ACR, Conte’s brigade made a sharp right turn toward a road junction called Objective Norfolk. Advancing into the darkness were two battalion task forces, one infantry and one armor. The 4-3 FA, in a tight formation, tucked in right behind them.

Conte and his Humvee driver used night vision goggles to stay with the howitzers as they approached Objective Norfolk. Sitting in their path, however, were several well-camouflaged Iraqi T-55 tanks that were bypassed in earlier fighting.

Those tanks unexpectedly opened fire on 4-3 FA’s M109A2 howitzers with 14.5 mm machine guns. American artillerymen returned fi re, and instantly the night sky filled with blazing tracer bullets along with the spark of lead striking steel. Conte said he and his driver, caught in the middle of this terrifying firefight, “bailed out of our Humvee and took up a fighting position behind the front tire.”

Eventually, the enemy T-55s all succumbed to overwhelming U.S. firepower. Conte and his comrades then resumed their mission.

In total, one British and three American divisions collided with 11 Iraqi divisions on Feb. 26 and 27, 1991. Historians would later describe it as the largest tank action fought by American forces since World War II. Those who lived through the Battle of Norfolk called it “Fright Night.”

[NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC: The Untold Story of the World’s Fiercest Tank Battle]

Superior allied training, doctrine, tactics, and weapons systems dominated the battlefield. At a cost of 21 soldiers’ lives, the U.S. VII Corps crushed Iraq’s Republican Guard. The enemy suffered thousands of casualties, with 550 tanks destroyed and an estimated 11,500 prisoners of war captured.

“I’m amazed I survived it,” Conte said while looking back on Fright Night 35 years later. He credits his soldiers’ discipline and fighting spirit as the keys to victory in Operation Desert Storm.

Lt. Col. Patrick J. Chaisson, USA (Ret), is a historian and writer based in Scotia, N.Y.

Military Officer Magazine

Discover more interesting stories in MOAA's award-winning magazine.