(A version of this article by Hope Hodge Seck originally appeared in the May 2022 issue of Military Officer, a magazine available to all MOAA Premium and Life members. Learn more about the magazine here; learn more about joining MOAA here.)

Col. Jim Carano, USA (Ret), is still undergoing procedures to treat the side effects of his 20-year battle with bladder cancer. At 45, CWO3 Chris Videau, USA (Ret), has had to give up running for good; he uses three different inhalers just to be able to breathe easily. Former Army Staff Sgt. Bill Bonk had his cancerous gallbladder removed in 2004, and then, four years later, went back into surgery to have his cancerous thyroid taken out. Capt. Le Roy Torres, USAR (Ret), was forced to leave his job because of his lung damage.

[JOIN MOAA ON MAY 28: Pass the PACT Act Rally, Washington, D.C.]

These veterans served in different eras, on different bases, and in different specialties. Their common ground is the debilitating health issues they have reason to believe were caused by poisons they drank, absorbed, or inhaled while in service with the U.S. military. And though they served and fought as part of large organized units in uniform, they’ve largely fought their battle with toxin-induced disease alone.

Veterans who spoke with Military Officer talked about the “Death Strategy” — their belief that the Department of Veterans Affairs stalls by commissioning studies, conducting inquiries, and taking refuge in uncertainty — to avoid extending costly health care coverage to millions of sickened veterans. Delay, deny, until we die, the saying goes.

[TAKE ACTION: Ask Your Senators to Pass the Honoring Our PACT Act]

But with a new, younger generation of veterans dealing with their own toxic exposure crisis from burn pits in Iraq and Afghanistan and an effective advocacy push from veterans organizations and grassroots groups that has made the issue front-page news, legislation to provide for vets exposed to toxins has its best chance ever of becoming law.

For many veterans, this help will arrive too late. And for an all-volunteer force, the perception that the nation does not keep its promises to those who serve could affect the choices of future generations.

“I think it’s a national security issue,” Jon Stewart, longtime host of Comedy Central’s “The Daily Show” and prominent advocate for veterans affected by burn pit exposure, told Military Officer. “The last thing you would want is for your all-volunteer military to feel like they are cannon fodder when useful. Because certainly the ethos that they instill in each other is ‘No one left behind.’”

The current VA secretary, Denis McDonough, has said that, regardless of VA’s history on the issue, he wants to prove the VA takes care of its own, even without congressional mandates.

“You fight for us, we’ll fight for you,” McDonough told members of the Military Officers Association of America at MOAA’s annual meeting on Oct. 21, 2021. “If you have our backs, we’ll have yours. The thing is, our nation as a whole makes that promise, but we at VA, at MOAA, are among those most responsible for keeping that promise.”

[RELATED: VA Secretary Outlines Priorities, Initiatives at MOAA’s Annual Meeting]

Early this year, the executive branch took major steps that indicate veterans’ advocacy is gaining traction. The White House added a presumptive service connection for nine rare respiratory cancers affecting veterans who served in Southwest Asia, allowing about 100 veterans whose claims were previously denied to receive VA care.

President Biden, whose son Beau served as an Army major in Iraq, suggested in March in his State of the Union address that burn pits caused the brain cancer that claimed his son’s life in 2018. He urged Congress to pass legislation that grants care to all veterans affected by toxic exposures, calling it a “sacred obligation.”

[RELATED: VA Adds 9 Respiratory Cancers to List of Conditions Related to Burn Pit Exposure]

It’s a hopeful development for veterans who have fought personal battles against service-connected illness for decades.

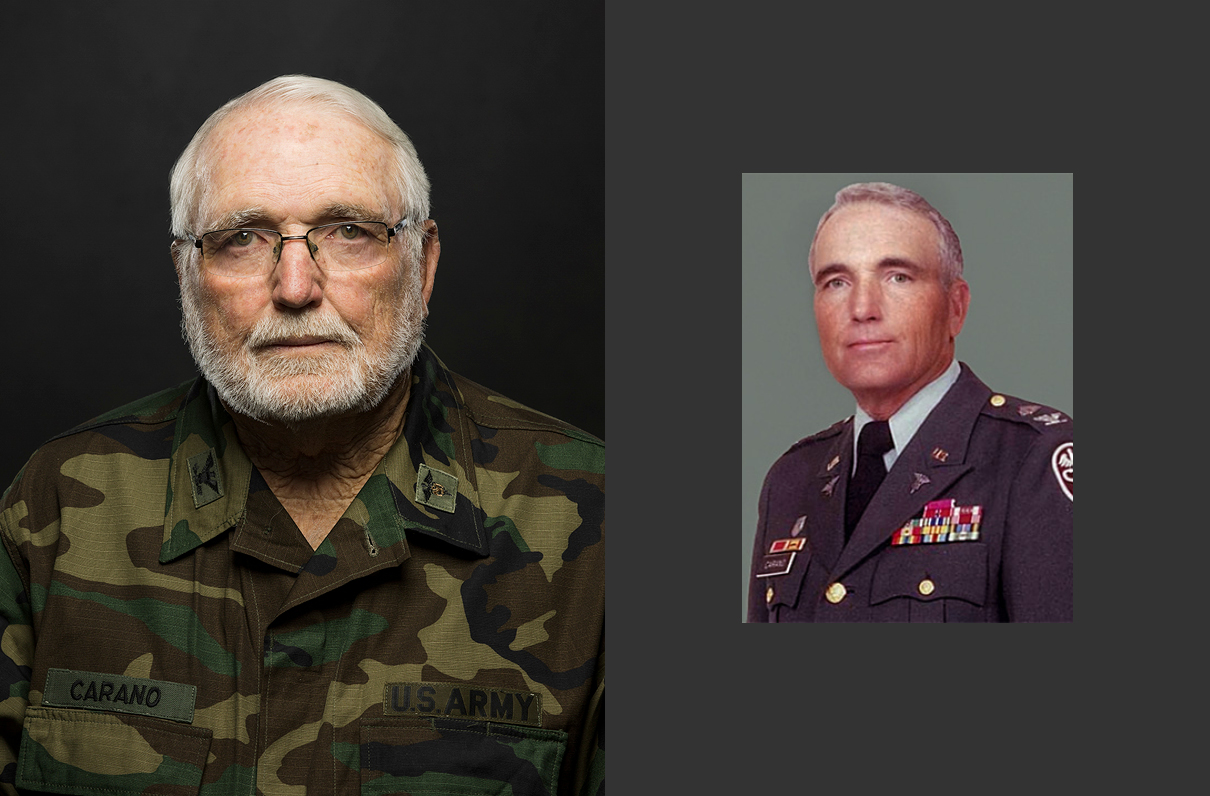

Col. Jim Carano, USA (Ret), was exposed to Agent Orange in Vietnam and diagnosed with bladder cancer in the mid-1990s. The VA only recently added the condition to its list of Agent Orange presumptives. (Left photo by Studio 3 Images; right photo courtesy of Jim Carano)

‘We Were All Exposed’

Carano spent his 367 days in Chu Lai, South Vietnam, under a dense orange cloud. Then a captain serving as the chief of the personnel division with the Army’s 23rd Infantry Division, Carano didn’t know much about the chemical that arrived on aircraft in orange barrels. But he was just miles from dense jungle on which the Army dumped the stuff from the air in an effort to kill the foliage and deprive Viet Cong fighters of a hideout.

“Boy, I’m telling you, we were all exposed to it,” Carano, now 79, said. “And we had not a clue.”

The year Carano hung up his uniform, the Institute of Medicine issued its first congressionally directed report on the impact of the chemical defoliant Agent Orange on veterans. By then, it was known that Agent Orange was contaminated with TCDD, a powerful dioxin known to promote the cancer-causing properties of other substances.

IOM, now known as the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, concluded there was sufficient evidence to link Agent Orange exposure to five medical conditions, including soft-tissue sarcoma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. For another two dozen conditions, it found, there was limited or insufficient evidence of a connection.

For bladder cancer, the study found “limited/suggestive evidence of no association” with Agent Orange exposure.

Less than a year after the 1994 report came out, Carano was diagnosed with tumors on his bladder. Two decades later, in 2014, bladder cancer was acknowledged to meet the scientific threshold. Earlier this year — nearly three decades later — he received a letter from the VA notifying him that bladder cancer had finally been added to the list of Agent Orange-related conditions.

The deployment of Agent Orange in Vietnam is perhaps the best-known and most thoroughly documented military toxic exposure incident, but cases of veterans sickened by exposure to unknown chemicals span nearly every generation of service.

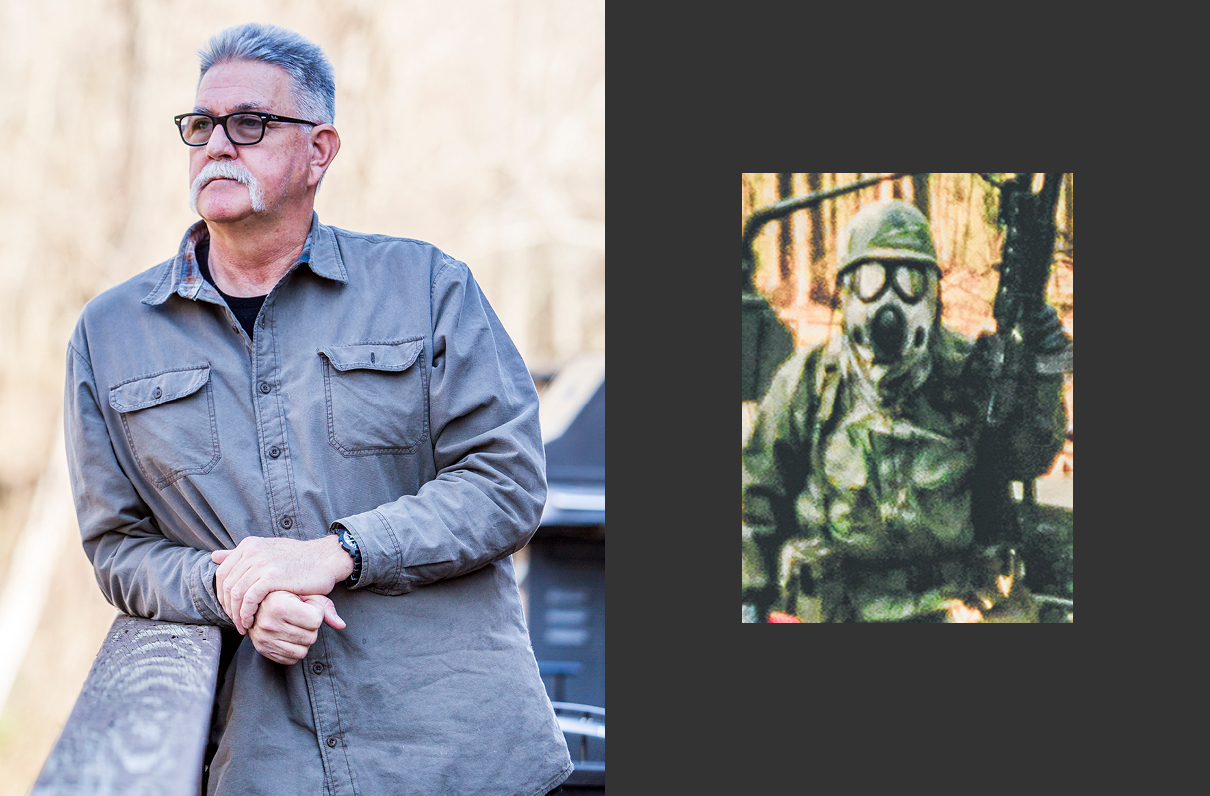

CWO3 Chris Videau, USA (Ret) was once told by a Navy doctor that his lungs resembled those of a 70-year-old. (Left photo by David Edward Photography and Videography; right photo courtesy of Chris Videau)

‘We May Get Lung Cancer’

For the sheer number of veterans exposed, the burn pits of the Gulf and post-9/11 wars represent the biggest blight on this toxic timeline. The Defense Department estimates some 3.5 million veterans were exposed to fumes from burning plastic, paint, fuel, human waste, and other garbage while deployed in the Middle East. A handful of burn pits are still in use.

Videau, who flew Black Hawk helicopters for the Army, remembered using the dense, acrid column of smoke from the burn pit at Camp Speicher in Tikrit, Iraq, as a visual navigation point when flying.

“We used to joke, you know, ‘Man, we may get lung cancer, instead of being [hurt] in combat,’” Videau said.

After returning from that deployment in 2008, Videau underwent a medical evaluation to determine why he got winded easily and struggled to breathe. A Navy doctor at the Alaska Army base where he was then stationed told Videau his lungs were those of a 70-year-old and suggested to him that the damage might be related to burn pits, adding that military health care providers were seeing these issues with increasing frequency in those who’d deployed to the Middle East. Ultimately, Videau was granted coverage for his health issues, but he said his file notes asthma acquired while in service and does not mention burn pits.

“I think that’s kind of a taboo, to put it in,” he said.

The physical harm Videau has endured as a result of burn pits inspired him to launch a business making dehydrated laundry detergent sheets that eliminate the need for plastic bottles like the ones that ended up in burn bits in Iraq. His company, Sheets Laundry Club, was featured on the entrepreneur show “Shark Tank” in 2021.

Videau considers himself fortunate, as veterans largely have had to prove individually that their encounter with a toxin resulted in their illness. The VA maintains a web page about the chemicals troops may have been exposed to at Fort McClellan, Ala., for example, but adds that “there are currently no health conditions associated with service” there. That’s despite the $700 million Monsanto and Solutia, Inc., paid to settle a class-action lawsuit with residents of the neighboring Anniston, Ala., in 2003.

Like many who served at Fort McClellan, Ala., former Army Staff Sgt. Bill Bonk was unable to convince the VA to cover his cancer treatments. (Left photo by Amy Brendel; right photo courtesy of Bill Bonk)

Bonk, who spent four months on the post as a member of the Military Police, remembered marching past signs indicating contaminated areas of the base, and conducting maneuver training on dump sites where radioactive isotopes had previously been buried.

“We didn’t have the benefit of questioning anything, really,” Bonk, now 60, said. “Especially being enlisted. Just a peon in the sea of green.”

His effort to convince the VA to cover treatment for his thyroid cancer demonstrates the difficulty of proving a nexus from contamination to illness without what the VA calls a “presumptive service connection.” No presumptives exist for Fort McClellan.

Bonk said he had a board-certified endocrinologist write him a three-page letter connecting specific events at the post with his cancer. The VA denied the claim. Now the administrator of a Facebook group for Fort McClellan veterans and a member of several others, Bonk said he has never seen a claim connected to exposure on the base approved at the regional level, although a few have been granted on appeal.

Movement in Congress

In March, the House of Representatives passed the Honoring our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics (PACT) Act, which would order the VA to cover 23 cancers and other respiratory diseases for veterans exposed to burn pits, and add hypertension to the list of presumptives for Agent Orange veterans.

It would also create a Fort McClellan health registry, among other study efforts, and add a toxic exposure questionnaire to routine primary care appointments at the VA. The legislation comes with a staggering price tag: about $208 billion over the next 10 years.

[UPDATE: Deal on Toxic Exposure Bill Includes More VA Staff, Dozens of New VA Clinics]

“For too long, America’s message to toxic-exposed servicemembers and veterans has been simple — we thank you for your service, but the price tag for addressing your exposure is just too high,” the bill’s sponsor, House Veterans Affairs Committee chairman Rep. Mark Takano (D-Calif.) said in a released statement. “We cannot accept legislative half measures that narrow benefits for some veterans and exclude others altogether.”

The White House released a statement of support for the bill Feb. 28. Senate Veterans' Affairs Committee leadership announced a bipartisan deal on a Senate version of the bill May 18 and released the text of the amended Honoring Our PACT Act on May 24.

MOAA has advocated for comprehensive reform packages, supporting legislation including the Honoring Our PACT Act. Reforms to the VA presumptive process that include a research advisory committee and greater transparency around toxic substance use and tracking are among MOAA’s top priorities for 2022.

Cory Titus, director of Veteran Benefits and Guard/Reserve Affairs at MOAA, said the organization wants three things: process reforms; a robust scientific process to ensure the right associations are made between toxic exposures and illnesses; and faster creation of presumptive conditions once the scientific burden has been met.

“Right now, it’s just far too complicated,” he said.

Capt. Le Roy Torres, USAR (Ret), founded Burn Pits 360 with his wife in 2010. He suffers from constrictive bronchiolitis related to burn pit exposure. (Left photo by Molano Media; right photo courtesy of Le Roy Torres)

The powerful multi-pronged push to pass new toxic exposure bills is thanks in large part to advocacy on behalf of the millions affected by burn pits. Grassroots groups like Burn Pits 360, founded in 2010 by Torres and his wife, Rosie, have drawn unprecedented attention to the issue.

After serving in the Army Reserve as a logistics officer for 16 years and deploying to Iraq in 2007, Torres lost his job as a Texas state trooper due to lung damage — constrictive bronchiolitis — related to burn pits.

The Supreme Court is now considering whether his forced resignation constitutes employer discrimination against a servicemember. As a reservist, Torres said, he was denied even care that would have been available to him as an active duty soldier after he came off orders.

“I will always be patriotic, but there was a sense of betrayal,” he said. “I had been betrayed.”

Stewart, who previously campaigned successfully to secure health benefits for first responders who inhaled toxic fumes from burning rubble and debris after Sept. 11, 2001, threw his weight behind the cause of burn pit veterans after Rosie Torres approached him.

Stewart underscores the significance of making the nation aware of veterans’ battles with toxic exposure.

“The less awareness there is over the suffering in that community, the less pressure there is to relieve it and go on with the status quo,” he said.

The veterans who spoke with Military Officer don’t regret their service. Torres, 49, has a son in uniform, and Carano has a grandson who was exposed to burn pits on deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan. They’re proud to see the military legacy continue. But advocates say the military risks its reputation and jeopardizes future recruiting efforts when it fails to care for those who served.

“The treatment of the last generation of veterans affects the propensity of the next generation to serve our country,” Titus said. “The Department of Defense is already trying to attract talented recruits from an ever-shrinking pool of candidates — as a nation, we don’t need to make it smaller because we’re refusing to take care of those who already served.”

Hope Hodge Seck is a defense journalist based in the Washington, D.C., area.

Military Officer Magazine

Discover more interesting stories in MOAA's award-winning magazine.