(This article by Christopher P. Cavas originally appeared in Military Officer, a magazine available to all MOAA Premium and Life members. Learn more about the magazine here; learn more about joining MOAA here.)

It began in March 2015 when a team of deep-sea searchers announced they had located the long-lost Japanese warship Musashi, one of the biggest battleships ever built, lost in battle in 1944.

Later in 2015, the same group brought up the bell from the battlecruiser HMS Hood, one of Britain’s most famous warships, sunk in battle with the German Bismarck in 1941. Both events made world headlines.

After a hiatus in 2016, the same group, now identified with their research vessel Petrel, discovered the wreck of a World War II Italian destroyer in the Mediterranean during March 2017. In August that year, they announced the discovery of one of the most elusive shipwrecks ever: the U.S. heavy cruiser Indianapolis (CA-35), sunk in the waning days of WWII with a heavy loss of life. The wreck, at a depth of 18,000 feet in the middle of the Philippine Sea, had long been considered to be one of the most difficult ships to find.

The Petrel operated in Philippine waters during the last three months of 2017 and into 2018 and racked up an impressive list of discoveries: the wrecks of the Japanese battleships Fuso and Yamashiro and destroyers Asagumo, Hamanami, Michishio, Naganami, Shimakaze, Wakatsuki, and Yamagumo. The team also found two American warships, the destroyer Cooper (DD-695) and high-speed transport Ward (ADP-16, ex-DD-139), famous for firing the opening shot at Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

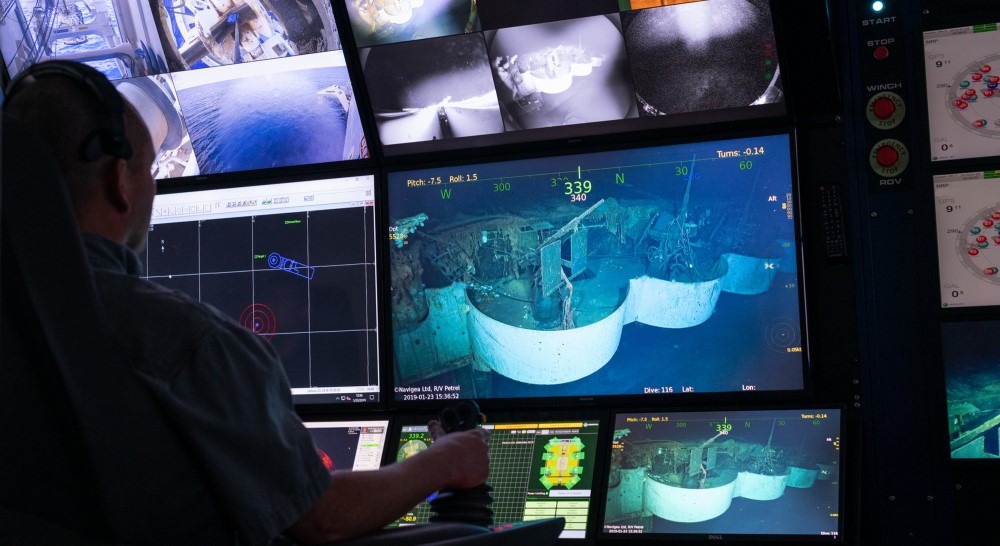

A Petrel team member guides a remotely controlled underwater vehicle while surveying the wreck of the aircraft carrier USS Hornet. (Photo by Navigea Ltd.)

The string of finds kept coming. After pausing to locate the wreck of a Navy C-2A Greyhound carrier supply aircraft that crashed in the Philippine Sea in November 2017, Petrel found the aircraft carrier Lexington (CV-2), one of the most famous Navy ships of the 1930s and the first U.S. carrier lost in combat, at the Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942.

Less than two weeks later, the group found the cruiser Juneau (CL-52), lost in November 1942 with the five Sullivan brothers. Weeks later, the group located the cruiser Helena (CL-50), sunk in July 1943.

The Petrel team then turned to the wreck of the Australian submarine AE 1, sunk in September 1914 off Papua New Guinea and discovered in December 2017. Petrel employed its unique sophisticated technology to create imagery to be used in developing a three-dimensional model of the wreck.

More impressive accomplishments came in 2019, when at least 16 previously undiscovered shipwrecks were found: U.S. aircraft carriers Wasp (CV-7) and Hornet (CV-8), escort carrier Saint Lo (CVE-63), destroyers Strong (DD-467) and Johnston (DD-557); and Japanese aircraft carriers Kaga and Akagi, battleship Hiei, cruisers Chokai, Furutaka, Jintsu, Maya, and Mogami, and destroyer Niizuki.

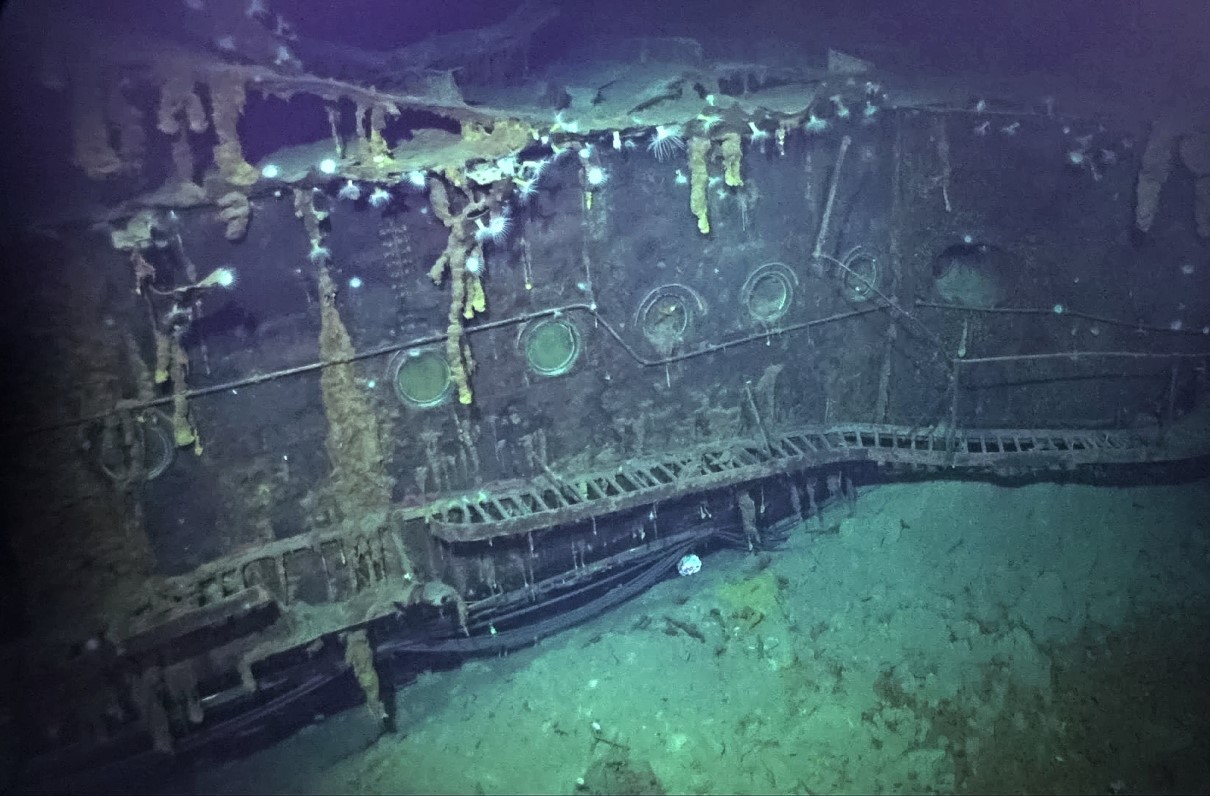

An International Harvester plane tractor aboard the USS Hornet, still chained to the hangar deck. (Navigea Ltd.)

The group also found and documented the wrecks of the Philippine ferry Doña Paz and tanker Vector, sunk in a 1987 collision in the Sibuyan Sea. About 4,400 people died in the sinking of the Doña Paz, thought to be the highest peacetime loss of life of any maritime disaster.

Along with locating the wrecks, Petrel created outstanding high-quality video imagery of the ships, far better than anything previously seen.

So Who Are These Guys?

Petrel is owned and operated by Vulcan, the corporate entity set up by Microsoft co-founder and multibillionaire Paul Allen. Among Allen’s many interests were WWII capital ships and aircraft.

Using his expeditionary yacht Octopus, he hoped to find and explore the undersea realm and, in particular, find the battleship Musashi.

Rob Kraft, an experienced commercial diver and operator of manned and unmanned undersea vehicles, was hired by Vulcan to oversee underwater activities. But neither Allen nor Kraft envisioned the wreck-finding juggernaut Petrel was to become.

“It really started out somewhat benignly,” Kraft explained. “The Octopus became a world-re-nowned expeditionary yacht, and Paul had this insatiable appetite for exploration and experiences in finding things. It was always, ‘What can we go look at? What can we go find? How can we contribute to the archeological community? We’ve got these great assets, what can we do?’ ”

The starboard door to the Wasp’s pilot house was left open as the ship was abandoned. (Navigea Ltd.)

Allen acquired ever-more sophisticated tools, including a Bluefin autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV).

“We bought it specifically with one purpose, and that was to go find the Musashi,” Kraft said. “Paul had this fascination with the Musashi. It was just a magnificent ship.”

Before heading to the Philippines to look for the lost battleship, the group went to Ironbottom Sound, the body of water in the Solomon Islands that became littered with wrecks of American, Japanese, and Australian warships during the Guadalcanal campaign of 1942-43.

Robert Ballard, famed for finding the wreck of the Titanic, had located a number of wrecks there in the early 1990s.

“We went out and mapped the entire sound,” Kraft said. “We rediscovered everything Ballard had found — I think the count was up to 27 wrecks we identified and found.”

[MORE HISTORY: Marking a Milestone: World War II, 75 Years Later]

The group then headed aboard Octopus to the Philippines and eventually located the Musashi.

“That was about a three-week project,” Kraft said. “I left the ship and flew from Manila to Tokyo. And I no sooner landed in Tokyo than I had an email from Mr. Allen asking, ‘What else can we do? What more can we do?’ That led into the deep-water assets we have today, and this mission and program was developed out of that.”

With larger ambitions, Allen needed a larger ship, one dedicated to exploration and research. The group in late 2016 purchased a former oilfield exploration and support ship that became the Petrel.

The effort, Kraft said, was based on Allen’s “appetite for exploration and research, and with the focus of the searches and targets we’ve been after, it’s really been a tribute to the men and women who served their country. And it was in remembrance of his father’s military service to our country. We thought it was very important to find these sites and bring back history for generations to come.”

At first the organization sought a minimum of publicity for their finds.

“We couldn’t talk about the things we were doing on Octopus,” Kraft said. “But when Petrel came into the picture, all of that changed. We didn’t even have a Facebook page!”

The effort has grown to include cooperation with video productions and outreach to schools.

Allen died of cancer in October 2018, but the Petrel effort is continuing and even growing.

“In three years this has just been a whirlwind, from absolute secrecy to developing this program,” Kraft said. “None of us ever signed up for this — it’s just kind of what we did. It has evolved, and very quickly.”

The group has developed an amazing knack for success where others have failed. One of the keys is doing as much primary-source research as possible before heading out to search for a wreck.

“It’s been a massive education,” said Paul Meyer, the group’s primary researcher and an experienced operator of undersea craft.

“Every time we do a different ship, it’s like cramming a four-year education into months. It was even more intense in the beginning, because when I was looking at something on a ship or part of a ship, [sometimes] I had no idea what I was looking at. But now it’s become second nature.”

But How to Find a Ship?

The reported locations of nearly all ship sinkings are always a bit off. To generate an estimated location, Meyer consults any original documentation he can find relating to a ship’s loss — log books and navigational charts of ships in the vicinity, communications logs, action reports. He looks at the weather and ocean currents. Timelines of the sinking are developed to ascertain what happened and in what order.

Even then, it’s not always obvious what turns up on the ocean floor. One such mystery was the carrier Wasp, lost when it was torpedoed in the South Pacific by the Japanese submarine I-19 in September 1942. The battleship North Carolina (BB-55) and destroyer O’Brien (DD-415) were hit in the same attack.

“We put the AUV in the water, and sure enough, we have debris in that first grid,” Meyer recalled. “We said, ‘Wow!’ So we followed that debris trail to the shipwreck. But in this case, it didn’t lead to a shipwreck — just trails of debris. We were starting to expand our search around that first grid. And it clicked for Rob ... There were two distinct trails, and he thought it was probably these two other ships that were torpedoed at the same time. We had a map of the orientation of the ships when it happened. And we thought the Wasp should be in this direction, and sure enough, we found it. As I recall it was about 14, 15 miles away. ”

Vulcan and the Navy have a mutually beneficial relationship. Vulcan makes all its materials available to the Navy’s History and Heritage Command, and Navy historians are on board for most of the Petrel’s searches.

Historian Frank Thompson was there in fall 2019 as Petrel searched for and found the wrecks of the Japanese carriers Kaga and Akagi, lost at the Battle of Midway in June 1942.

“One of the things that really shocked us all was the degree of utter destruction of the ship above the main deck,” Thompson said about the Kaga. “From what we saw, everything above the main deck is pretty desolate. The destruction is complete.”

While finding the wrecks is exciting, seeing the fatal damage and the deaths involved is a sobering experience.

“You think about the last time human beings saw these ships, they were ablaze and taking damage. Then you see them on the ocean floor,” Thompson said.

Meyer agreed.

“You see the shell hits, the holes in the hull. You can see where the ship has been burning. And you can easily put yourself there at the time and imagine [that] it must have been horrific.”

Christopher P. Cavas is a naval journalist and commentator based in the Washington, D.C., area. He’s on Twitter @CavasShips.

MOAA Knows Why You Serve

We understand the needs and concerns of military families – and we’re here to help you meet life’s challenges along the way. Join MOAA now and get the support you need.