(This article by Kathie Rowell originally appeared in the April 2020 issue of Military Officer, a magazine available to all MOAA Premium and Life members. Learn more about the magazine here; learn more about joining MOAA here.)

Andrew Carroll found his life’s mission when his family lost everything in a 1989 housefire.

A college student at the time, Carroll mourned the destruction of irreplaceable family photos and letters, which led to an interest in family history. That spurred a distant cousin who was a World War II veteran to share a letter he had written to his wife in April 1945. It contained his vivid eyewitness account of the horrors of a just-liberated Buchenwald concentration camp where prisoners were still dying.

For Carroll, who had never cared for history’s dry dates and facts, the letter was a revelation of the human side of war.

“I said, ‘This is one of the most extraordinary things I’ve ever read and, of course, I’ll send it back to you.’ And he said, ‘You know, just keep it. I probably would have thrown it out anyway.’ The fact that people are throwing [historic war letters] away just really struck me.”

That exchange started a lifelong quest to save these intimate pieces of history and led in 2013 to the establishment of the Center for American War Letters at Chapman University in Orange, Calif.

‘The Floodgates Opened’

At first, Carroll used word of mouth to tell others about what he called the Legacy Project. In 1998, he wrote a letter to the Dear Abby advice column about the project, and she asked readers to send their letters to a post office box Carroll had set up.

“Three days later, the post office called,” Carroll said. “They were getting inundated, and it was just like the floodgates opened.”

Until the center was founded, he worked on the project in his spare time while holding down other jobs. Now Carroll is the founding director of the center, which houses about 150,000 pieces of correspondence representing every American conflict, from the handwritten letters of the Revolutionary War to the emails sent from Iraq and Afghanistan.

That may sound impressive, but Carroll isn’t complacent.

“There’s unquestionably millions of war letters out there tucked away in attics and basements and closets,” he said. “Sixteen million people served in World War II, and even if every one of them just sent a single letter, that’s 16 million letters right there. It’s possible there could be up to a hundred million war letters just kind of tucked [away] out there, and they are so important because I think they really help this generation and those to come to better understand the sacrifices that our troops and their families make in times of war.”

Among the letters collected:

- A Civil War letter found on the battlefield.

- A World War I letter in which the wounded writer talks about a fellow patient who had “247 wounds” and “2 pounds of lead” removed from his body. The author’s name? Ernest Hemingway.

- A World War II letter with a bullet hole through it.

- A letter describing missiles flying overhead from a woman serving on a Coast Guard patrol boat during the Gulf War.

Emotions on Paper

One letter in the collection is from Col. Zoltan Krompecher, USA, a MOAA member who wrote a letter to his children to be opened if he did not return from deployment. A poet friend with whom he had shared it submitted the letter to a National Endowment for the Arts project called Operation Homecoming, and the next thing Krompecher knew, he was being interviewed by CBS News.

He met Carroll, and the letter became a part of the War Letters Project.

A Green Beret, Krompecher wrote the letter and placed it in a lockbox on a closet shelf in 2004, just before deploying to Iraq, because he realized his focus on what lay ahead had distracted him from spending time with his kids in the present.

Lt. Col. Zoltan Krompecher, USA, right, accepts the battalion colors from Lt. Gen. William Caldwell IV, USA, during a change of command ceremony for U.S. Army North at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, in 2012. (Photo by Staff Sgt. Corey Baltos, Army North)

“You train your whole career, and you just want to test your mettle in combat, but the irony is that the folks for whom we’re going to go fight are the ones who we are leaving and the ones we may never return home to,” Kromprecher said. “It’s hugs, kisses, prayers, and an heirloom in the rucksack until you come home, but not everybody comes home alive or whole.

“So, I was looking at my kids and the fact that, all this time, they had been asking to play with me. … And in my mind, I’m thinking, ‘Man, I’m going to Iraq.’ ... I was putting my daughters to bed, and they were crying about my leaving, and I realized I blew it. So I wanted to make sure that I left the letter, knowing they could open it and know that they had a dad who loved them, and I’m sorry.”

Krompecher said the letter wasn’t hard to write, despite its grim purpose.

“I just stayed up one night and poured those emotions out onto a sheet of paper,” he said. “It was a great reminder of why you’re going over and when you come back, you need to be a better dad, a better husband, or just a better person in general.

“I hoped it would never get to the point where they actually had to open it, but if they found themselves fatherless, I hoped they’d read it from time to time throughout their lives and know that they had a father who loved them very much, and they could move forward in life just knowing that I was there watching over them.”

Krompecher calls the War Letters Project a tremendous gift of living history.

“They are personal letters and they are their stories, but, in the larger sense, they’re our stories, too. It’s America’s story. They offer a glimpse into what it’s like to serve, what it’s like to leave everything you’ve known and walk into situations with people — who a few months prior were complete strangers — and to serve a higher purpose.”

[More About Military Officer Magazine]

War and Peace

The collection also includes Vietnam-era audio letters from one of the most iconic names in U.S. military history.

Benjamin Patton, grandson of Gen. George S. Patton Jr. and son of Maj. Gen. George S. Patton IV, shared the reel-to-reel and cassette tapes his father and mother, Joanne, sent back and forth to each other during three tours in Vietnam.

“He would record the experiences he had during a certain week, often right in his tent, and you could hear the mortars firing and the helicopters flying overhead. He would send it to my mom, and then my mom would send it back with the other side of the tape filled with her reflections and sometimes little interviews with the kids talking about what was happening in our lives.”

The audio letters are special to Patton because they give him a window into what his family was dealing with before he was born and when he was too young to understand.

They also highlight the juxtaposition of war and peace.

“My mother was in Washington, D.C., raising kids during the Vietnam era, and my dad was often right in the middle of a major war zone. And both of them are calm, and both of them, in a certain sense, are excited [about] where they were. He was a career soldier, so that’s what you serve to do — to go to war and to fight for freedom — and my mother was raising five kids, and you just sort of appreciated the respective challenges that they were both facing in very different settings.”

Patton allowed the War Letters Project to have access to the audio files because he thought they needed to be shared.

“They’re very particular in one way, but, in another way, it’s a universal experience of families being separated and wanting to be understood from a distance and to feel some sense of home and connection to someone, even though you’re in a battle zone.”

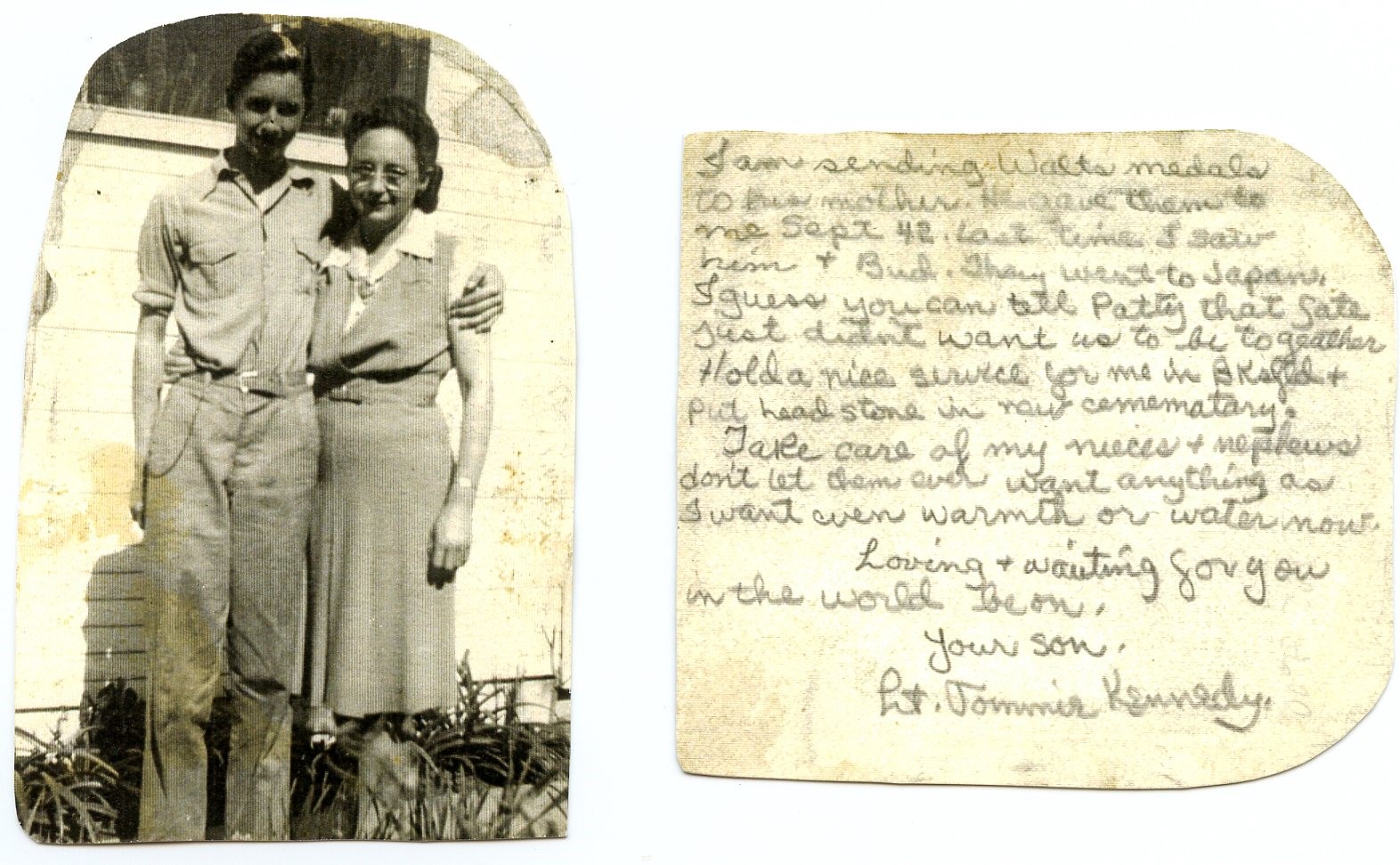

A young World War II soldier and POW named Tommie Kennedy wrote his last letter to his parents on the back of two photographs. He knew he was about to die, so he gave the letter to a fellow POW, who made sure it was delivered to his parents. (Images courtesy of the Center for American War Letters at Chapman University)

The Search Continues

Carroll, who has visited all 50 states and 35 foreign countries in his quest, is still diligently seeking more letters, traveling around the country with what he calls “the football” — a leather satchel containing some of the most compelling examples.

“Whether I go to a school or to West Point or to a veterans group, I show people actual letters,” he said. “We have the famous letter that has the bullet hole right in the middle of it. I want people to see the actual letter.”

[RELATED: MOAA Life Member, Retired Chief Flight Nurse Reflects on Her Family's Service]

He feels a special sense of urgency now as World War II veterans slip away, putting both their letters — and potentially their parents’ World War I letters — at risk as their possessions are dispersed.

He’s also committed to obtaining more correspondence from recent conflicts. That’s been a bit of a challenge, he said, because younger generations don’t believe what they wrote is as eloquent as what their great-great grandparents wrote in the Civil War or what their aunt who was a war nurse in Vietnam wrote.

“They just feel like their emails aren’t as important, but some of the emails I’ve read are as profound and as poetic as anything that’s come before. We really want to make sure the younger generation understands we want to preserve their correspondence as well.”

After 30 years of pursuing his passion, Carroll has come to realize that “everything is more vivid through the prism of warfare.”

“The love letters are more passionate. The philosophical letters are more profound. The letters to children are more poignant because the stakes are so high. Originally, I was interested in letters when the house burned down and we lost all our letters. But I think what really made me drawn to war letters is they show the full spectrum of human nature itself. And, like all great works of art, they ... transcend any one subject matter, so these really aren’t just war letters. These are letters about human nature.”

How to Share Your Letters

Carroll is actively seeking donations of any type of correspondence related to war or military life — from boot camp to being under fire to reflections on wartime experience. Topics have included love, humor, faith, death, homesickness, grief, anger, courage, peace, humanity, resilience, camaraderie, reconciliation, patriotism, and historical events. Letters from spouses, parents, children, siblings and other loved ones are also requested because they show the sacrifices of those left at home.

Handwritten letters, audio recordings, and emails are all accepted. Originals are preferred because scholars can better authenticate the material, and often discover additional information about a letter based on the paper itself and any embellishments. Letters are also used in exhibits, and originals have more of an impact on viewers. However, photocopies, scans, and transcripts of correspondences are accepted.

Carroll also welcomes help spreading the word about the project and is available to speak to groups or at events across the country.

To learn more, visit www.warletters.us. For donation and research inquiries, email warletters@chapman.edu or call (714) 532-7716. For appearances by Carroll, email warletterproject@aol.com.

Kathie Rowell is a freelancer based in Shreveport, La.

Support The MOAA Foundation

Donate to help address emerging needs among currently serving and former uniformed servicemembers, retirees, and their families.