Hubbard did survive the next six-plus years he was imprisoned. In spring 1973, he was among nearly 600 Americans released from prison camps in Vietnam. He flew home to the U.S. March 4, 1973.

Five decades later, on March 4, 2023, he once again flew home from Vietnam — but this time from a stay he had chosen to make in the country.

Hubbard was among eight former prisoners of war (POWs), along with spouses, friends, and family members, who traveled to Vietnam on a Mekong River cruise to commemorate Operation Homecoming and the release of POWs from North Vietnam.

FIFTY YEARS LATER

Hubbard was joined on the trip by Cmdr. William Shankel, USN (Ret); Col. Dewey “Wayne” Waddell, USAF (Ret); Lt. Col. Thomas Hanton, USAF (Ret); former Lt. Albert Molinare, USN; former Capt. David Drummond, USAF; Maj. Peter Camerota, USAF (Ret); and Col. Robert Certain, USAF (Ret), a former MOAA board member and national chaplain who organized the trip.

Certain had never returned to Vietnam following his release in March 1973.

“Fiftieth anniversaries are all really kind of big deals,” he said. “My wife and I just celebrated our 50th wedding anniversary in May [2022]. We were married just before I was deployed to Guam. … [This trip to Vietnam was] an opportunity to go and see how this country has changed and prospered in the last 50 years or so and to see some things that I’d never seen before.”

As a then-captain who was a navigator on a B-52G, he had flown over Cambodia, South Vietnam, Laos, and a little over North Vietnam, but he was never on the ground in Vietnam except in Hanoi — and that trip wasn’t supposed to happen.

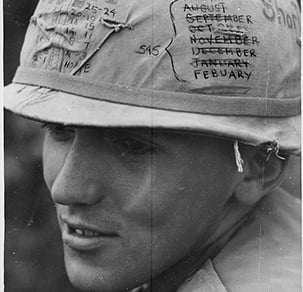

Certain was slated to rotate back home Dec. 18, 1972, but on his way to Hanoi with 128 other bombers, a surface-to-air missile hit his B-52, knocking out its instruments. “My first thought was the generators failed, but then the copilot started yelling, ‘They’ve got the pilot. They’ve got the pilot,’ and the electronic warfare officer was asking, ‘Is anybody alive?’ I looked over my left shoulder to the bulkhead door leading into the forward wheel well, and then through the porthole in that door, I could see flames. I knew we’d been hit.”

Certain ejected almost immediately after the bombs dropped, nearly 6 miles from the ground. When his parachute opened, he realized he was in a bad spot. “I looked down, and I was hanging right over the target and watching bombs walk right through the middle of it. I finally touched down probably 10 to 20 kilometers west of the target and was surrounded fairly quickly by civilians and four militia with automatic weapons.”

Spending less than a year in prison, Certain was one of the “new guys” on this anniversary trip to Vietnam. The worst treatment of prisoners mostly ended with the death of Ho Chi Minh in 1969, so the new guys were not subject to the brutality endured by the longtime POWs, or “old guys,” like Hubbard, Shankel, and Waddell.

“It took a long time for us to think we were worthy to be counted in their number [of those who spent years in prison],” Certain said. “We never went through anything like they did, but then they assured us that you spend a day there, you’re one of us.”

Waddell, an F-105 pilot who was shot down during a bombing run July 5, 1967, agreed. “Most of the people I know had the attitude ‘there’s no such thing as a little bit pregnant’ and accepted the newbies as one of us,” he said.

BACK TO THE HILTON

Following a Mekong River tour and a visit to Angkor Wat in Cambodia, most of the group flew to Hanoi to mark the 50-year anniversary. The two days spent in Hanoi were filled with stops in and around the city: the John McCain marker next to Truc Bach Lake where the future senator was pulled out and captured, the wreckage of the last B-52 shot down over the city, and a memorial to civilians killed by an errant bomb.

At the B-52 Victory Museum, the centerpiece of which is a B-52 pieced together from the wreckage of several planes, Certain and fellow B-52 crew member Drummond tried to figure out if any of the parts belonged to their planes.

As they toured the museum, Robbie Certain found a photo of her husband and other B-52 crew members shot down that December. A little later, Robert Certain found another prominent display of his picture. “I was a little surprised to see my name and my face as many times as I did, but I was the first B-52 crew member to be captured, and Tom Simpson, my electronic warfare officer, was second, so we were big news for Vietnam,” he said.

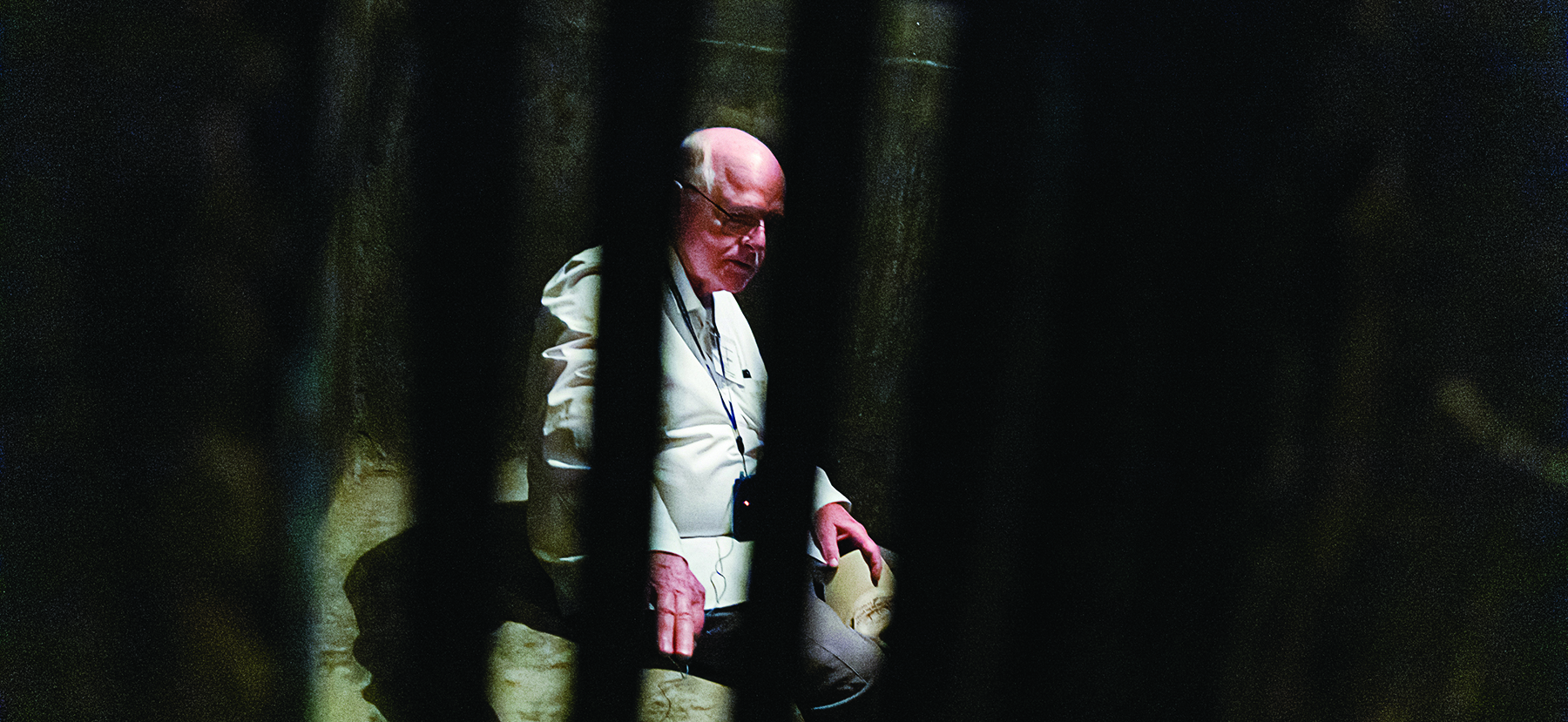

The most meaningful stop was what remains of Hoa Lo Prison, also known as the Hanoi Hilton.

Hoa Lo was built by the French in the 19th century during the colonial period in Indochina. After the French were driven out, the North Vietnamese used it to hold American POWs during the war. It remained in use until the 1990s. Now much of the prison is gone, converted into a museum that focuses mostly on the colonial period.

For the old guys on the tour, Hoa Lo Prison was the site of unspeakable brutality.

Waddell recalled being blindfolded and transported to the prison by truck.

“You hear these big doors close behind you, and then you hear another set of doors, heavy metal doors, out in front of you, and the truck moves in, and those double doors close again,” he said. “And it’s a very realistic confirmation that you are now in prison.”

As a fighter pilot, Waddell possessed a healthy bravado, but a few days into his captivity, he paid dearly for it. Prisoners strived to abide by the code of conduct and provide only name, rank, serial number. The interrogator ordered him to write his autobiography, but Waddell refused. “I decided I was going to act like an Air Force fighter pilot, and I said ‘I ain’t gonna do that.’ ”

The camp commander entered the room and ordered him to write, and he refused again. The commander told Waddell he would be very sorry.

“Later that day, I was very, very sorry,” Waddell said. “To put it simply, they broke me. They put me in a position I can’t even demonstrate properly. But I lost use of my hands for about three months or so.”

As they disembarked from the tour bus, Shankel, Certain, and Drummond stopped for a photo out front and then moved inside for the tour. They gathered around a model of the prison and pointed out to their wives and friends where they had been held over the years, using their names for the different sections: Little Vegas, where each room was named after a different Las Vegas hotel — Golden Nugget, Riviera, Stardust; the section called New Guy Village; the Heartbreak Hotel; and the so-called quiz rooms where POWs were interrogated or “quizzed” and, in the case of the old guys, brutally tortured.

As they made their way around the museum, word got around to other visitors that these Americans were former “guests” at the Hilton. Some asked for pictures with some of them or asked about their experiences at the prison.

While many of the exhibits downplayed any mistreatment of American POWs, some realities of the experience could not be erased. Drummond said revisiting Hoa Lo brought back a lot of memories. “It makes me feel old and brings back some unpleasant memories, but at least I’m leaving it behind,” he said. “I’m not carrying it with me for the rest of my life — that was one of the purposes coming here.”

Certain found his way into one of the few remaining cells and sat for a moment. “Going to what’s left of the Hanoi Hilton was less moving than I had hoped for because every place that I was held was gone,” Certain said. “But the dungeon cells were similar to where I was in what we called the Heartbreak Hotel, so I was able to show Robbie what the cells kind of looked like during that time. And that was one of the things I hoped for — to share more completely with my wife what those 100 days were like and what it meant to me.”

MOVING FORWARD

Nguyen Hong My, a former MiG pilot, spoke to the group at a farewell dinner in Hanoi. He stressed in his remarks a sense of reconciliation and of looking toward the future. For him, that meant meeting one of the American pilots he had shot down and becoming friends with Brig. Gen. Dan Cherry, USAF (Ret), who downed Nguyen’s MiG-21.

Hanton stopped in Hanoi on his way to the river cruise and reunited with Gen. Pham Phu Thai, the MiG pilot who shot him down in 1972. They had met previously in 2018, but Hanton’s schedule didn’t allow for a visit then to the Hilton. This time, they met at the former prison as fellow fighter pilots and friends instead of adversaries.

“I learned that they’re just like every other fighter pilot I’ve ever met,” Hanton said. “They were trying to outperform us. They were doing their mission, and had the tables been turned, I wasn’t trying to do anything specific to him.”

While reflecting on the trip, Certain said: “It’s like [Nguyen] said, ‘When we were warriors, we did what the leadership told us to do. But when the war ended, we’re not enemies anymore, so now when we meet, we can be friends.’ And that’s been my attitude for a long time.”

Hubbard recalled advice a fellow prisoner gave him: “He said, ‘When you leave here, don’t take any of this stuff with you. Go home and enjoy life and learn to live with it. Don’t waste your time hating the Vietnamese because they’re just doing their job,’ and I took that seriously.”

Mike Morones is MOAA’s multimedia producer.