For five decades, Harvey Pratt sketched drawings of the country's most brutal murderers, including Ted Bundy, the “BTK” killer and the Green River Killer.

But in his latest work, the Marine Corps veteran and member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, will honor his heritage and Native Americans veterans.

After reviewing submissions, Pratt's vision was selected for the Native American Veterans Memorial, which will be constructed outside the National Museum of the American Indian by late 2020.

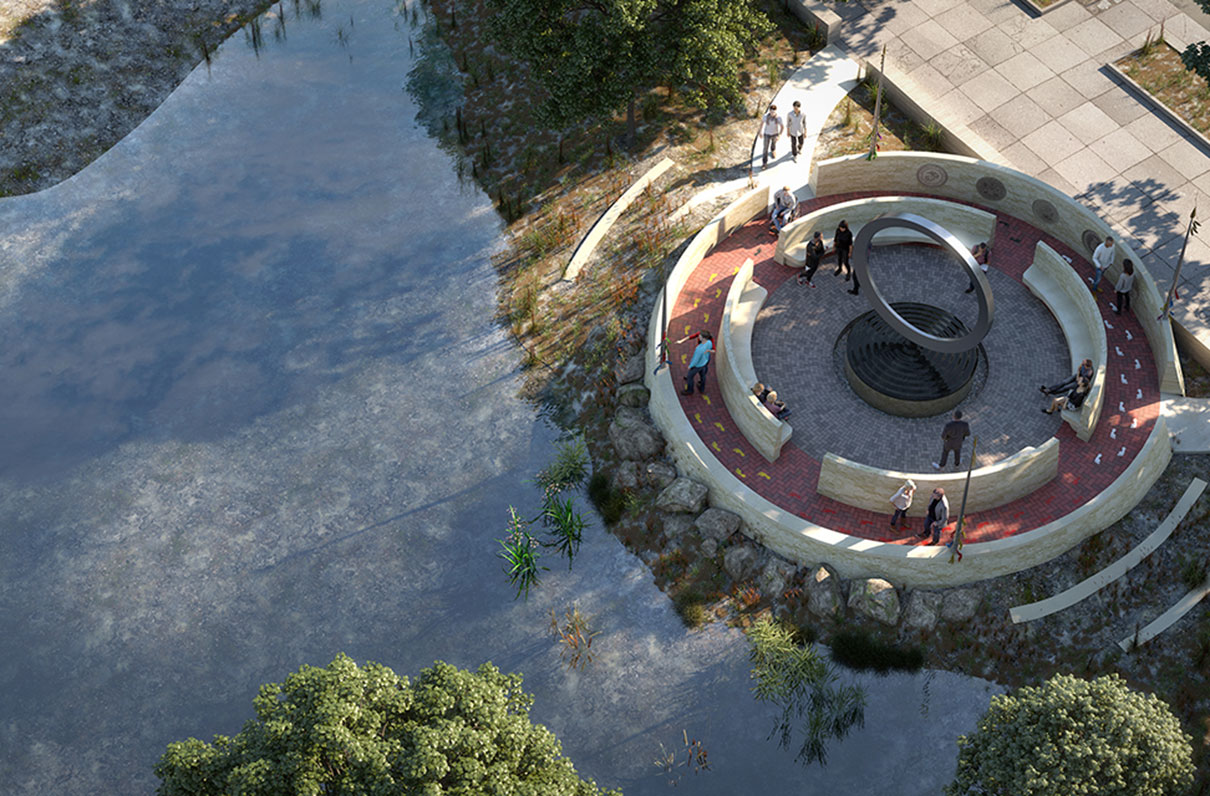

The design, “Warriors' Circle of Honor,” features a steel circle above a drum that will ripple water. It will also have a flame burning in the center of the circular monument. It incorporates four elements - earth, wind, fire and water -representing all federally recognized Native American tribes.

The memorial is interactive, encouraging people to get close and say prayers.

“People can walk in and be part of the monument, not just walk by,” Pratt said, from his home in Oklahoma. “If everybody came in there and prayed, it'd become a sacred place of healing. People could come in and feed their spirits and participate in this memorial. As people prayed and did ceremonies, it would be a powerful place. I wanted the National Veterans memorial to be the same way - a place of comfort, power and strength.”

This will be the first national landmark in Washington, D.C. that focuses on honoring American Indians, Alaska Natives and Native Hawaiians who have served in the military.

Not All Services Included

The monument is not without its critics. The memorial features seals for the five Armed Services: Army, Air Force, Navy, Coast Guard and Marine Corps.

It does not, however, include the U.S. Public Health Service or the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which are included in the broader Uniformed Services.

The Commissioned Officers Association of the U.S. Public Health Service is disappointed its officers - which have a large membership of Native American officers - is not included in the design.

On Aug. 21, Jim Currie, executive director of the association, met with staff of Senate Committee on Rules and Administration to discuss his concerns.

There are more than 800 Native American officers in Public Health, Currie said, which is about 12 percent of the active-duty corps and likely the largest percentage of Native Americans in any of the seven uniformed services, Currie said.

Currie said the committee has promised to look into his concerns regarding the memorial design.

The Military Association of America also belives NOAA and USPHS should be considered as additions to the memorial.

“While MOAA commends the artist for his design, and the intent to honor Native American service members, we encourage the Smithsonian to add the emblems of USPHS and NOAA as they are two of the seven uniformed services whose Native American members also serve this country with dedication and distinction," said MOAA President and CEO Lt. Gen. Dana T. Atkins, (USAF, Ret.). "As inclusivity is the theme with so many memorials, we believe this to be the perfect opportunity to recognize each of the seven uniformed services.”

A spokeswoman for the museum confirmed the design concept is still under review and has responded to Currie's concerns. The monument concept will be shared with organizations such as the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, the National Capitol Planning Commission and the DC State Historic Preservation Office.

From an MP to an Artist

Harvey is a self-taught artist, who traces his career to high school when he sold his first painting. He credits his success to his wife Gina, who has always supported him, he said.

In 1962, Pratt followed his uncle's footsteps and enlisted in the Marine Corps. He was sent to the 3rd Marine Division and was assigned to a military police unit, but during basic training, he was recruited for a special unit and sent to guerrilla warfare school.

He trained with that unit for two months.

He and about 45 other Marines from the guerrilla unit were sent to Vietnam, where they worked on an airbase, protecting work zones and picking up downed pilots. The men were deployed for seven months.

Pratt served in the Marine Corps for three years and left as a lance corporal. When he returned home, he started working as a patrolman for a police department in his home state of Oklahoma.

He continued working on his art in his spare time. He was sketching at work when a detective passed by his desk and asked if he could draw a description of a suspect from a victim's eyewitness account.

“I made the drawing based on her description,” Pratt said. “We were able to catch that guy.”

Over the next 50 years, Pratt would continue using his artistic talent to help track down serial killers. He also drew age progression images to help find missing children and even identify decomposed bodies by creating sketches with soft tissue repair.

He created 5,000 sketches, including Gary Ridgeway, the Green River Killer; Randall Woodfield, the I-5 Killer; Ted Bundy; and Osama Bin Laden.

“It's been extremely rewarding to me to help solve these cases,” he said. “To me, they're all rewarding. When you find a child that has been missing for 10 years and do an age progression to find [the person], that's rewarding. I have that same feeling of satisfaction on every case. I've just been blessed to have a wonderful career.”

After his retirement, Pratt dabbled in different types of art and even spent time chasing Bigfoot.

“I have never seen Bigfoot, but if I believe my ancestors, the big guy is still around,” Pratt said.

He's also focused on his art, using themes tied to his own Native American heritage. He recalls the kind, supportive words of an elementary school teacher.

“I had a varied career in the different types of art,” he said. “I don't think I ever got stagnant. I think it's important that kids are told by somebody that they have a skill or a talent. I didn't realize until a school teacher told me.”

Amanda Dolasinski is MOAA's staff writer. She can be reached at amandad@moaa.org. Follow her on Twitter @AmandaMOAA.